When people think of forests, they often imagine towering trees, rustling leaves, and the calls of wildlife. But beneath the forest floor lies something even more fascinating – an underground communication network scientists have nicknamed the ‘wood wide web.’ This hidden system of roots and fungi allows trees to share nutrients, send signals, and, in some sense, ‘talk’ to one another.

The Mycorrhizal Connection

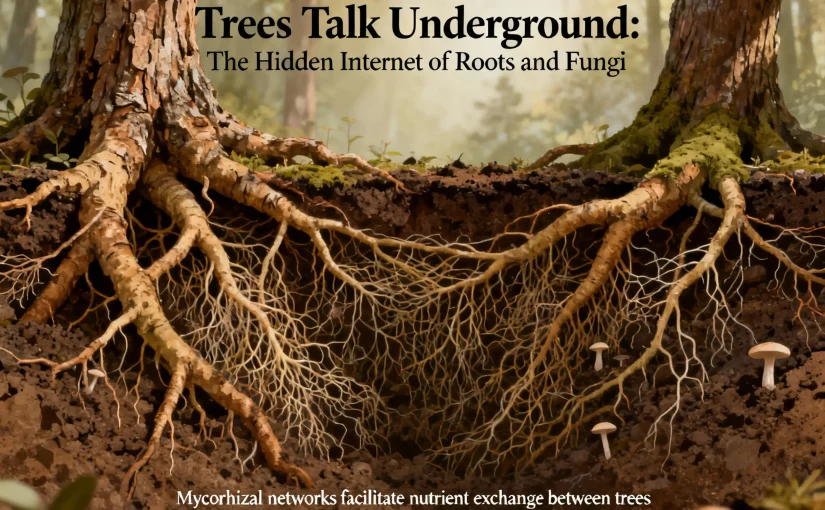

At the center of this network are mycorrhizal fungi (from the Greek mykes = fungus and rhiza = root). These fungi form symbiotic relationships with about 90% of plant species by colonizing their roots. The fungi receive sugars and carbohydrates produced by trees during photosynthesis, and in return, they help the plants absorb water, phosphorus, and nitrogen far more efficiently than roots alone could manage.

But the relationship doesn’t stop at trade – it extends to communication. Thin fungal filaments called hyphae physically link the roots of different plants, creating underground networks that can span entire forests.

Sharing Resources Among Trees

One of the most intriguing discoveries about these fungal networks is that they allow trees to transfer resources between one another. For example:

- Mature, healthy trees have been found to send carbon to younger seedlings struggling in shady conditions.

- Different species can share resources – such as when a birch helps a fir tree survive the winter by sharing carbon, and the fir reciprocates by offering resources in summer.

This cooperative behavior challenges the traditional idea that trees only compete for sunlight, water, and nutrients. Instead, forests may behave more like cooperative communities than battlegrounds.

Warnings in the Woods

Beyond resource-sharing, evidence suggests that fungi also help mediate chemical signaling. Some trees under attack by pests or disease seem capable of sending warning signals through these underground networks. Nearby trees then respond by boosting their own chemical defenses, such as producing bitter compounds that discourage herbivores.

This form of ‘immune system alert’ improves the overall resilience of the forest and highlights the ecological benefits of fungal connectivity.

Key Research and the Scientists Behind the Idea

The concept of underground communication networks was popularized by Dr. Suzanne Simard, a forest ecologist from the University of British Columbia. Her pioneering experiments in the 1990s demonstrated carbon transfer between paper birch and Douglas fir trees via shared fungal networks.

Since then, her work and that of others have revealed just how widespread and sophisticated these connections are. While the metaphor of an “internet” is imperfect, it captures the idea of information flow and connectivity within forest ecosystems.

Why It Matters

Understanding the ‘wood wide web’ is more than a matter of curiosity – it has real implications for:

- Conservation: Protecting forests means protecting not just trees but also the fungal networks that knit them together.

- Forestry practices: Clear-cutting can destroy these underground connections, slowing reforestation and reducing soil health.

- Climate change research: Resource-sharing among trees may influence how forests adapt to rising temperatures and extreme weather.

A Living Network Beneath Our Feet

The next time you walk through a forest, consider the invisible structures below you. Each step rests on a living, dynamic system that allows trees to nurture one another, defend themselves, and even shape the destiny of the entire ecosystem. Far from solitary giants, trees are active participants in a vast underground conversation – one conducted not with words, but with roots and fungi.